Encounter with Disease-Transmitting Arthropods

Okuda:

Dr. Kanuka, I understand that after graduating from the Veterinary Medicine program at the University of Tokyo, you conducted research on apoptosis at Osaka University and RIKEN. Could you tell us what led you to your current line of work?

Kanuka:

When I was in graduate school, I happened to learn about the concept of disease-transmitting arthropods. The realization that insects could carry diseases thrilled me, and I felt an almost fateful conviction—“This is what I’m going to do.” The moment I understood the process—diseases, infectious agents, and vectors transmitting them—I thought, “This is exactly what I want to pursue.”

Okuda:

Could you tell us more about what you felt at that time?

Kanuka:

My motto is “You excel at what you love.” If you truly love something, things naturally go well. And what does “love” mean here? Ultimately, it’s about whether something can completely absorb you when you encounter it or learn about it. When adrenaline and dopamine kick in, your motivation rises and drives you into action—and that energy helps you overcome hardships. Even when people see the same phenomenon, some become engrossed while others don’t. I don’t think we can ever fully explain what exactly moves a person’s heart.

Okuda:

I see. Besides interest, what other elements do you think are involved in becoming absorbed in something?

Kanuka:

What I call “love” may be less about free will and closer to determinism. My fascination with disease vectors hasn’t faded even after more than 20 years, so I sometimes think it’s simply part of my innate nature.

But one essential point is how you encounter what interests you—what I call “luck, connection, and timing.” Even if I had learned about disease-transmitting arthropods as a child, I doubt I would have been as captivated as I was. The window of timing matters greatly.

If you discovered this field in your 50s, even with ability, switching research areas would be difficult. In that sense, I was fortunate to encounter something I genuinely wanted to pursue while still a graduate student.

Seeking a Place to Do What I Wanted

Okuda:

After completing graduate school and studying abroad, why did you move directly from the University of Tokyo to Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine?

Kanuka:

After returning from abroad, I joined the University of Tokyo intending to start mosquito research on disease transmission. But after various complications, I was ultimately told it couldn’t be done there. At the time, labs working on mosquitoes in molecular biology typically used genetically modified Anopheles or Aedes species. I applied for approval to conduct similar work, but it was never granted.

Just as I was feeling stuck, I received an invitation from Obihiro University. They had a dedicated Research Center for Global Agromedicine specializing in infectious disease research, including disease-transmitting arthropods like mosquitoes and ticks. I accepted immediately.

Okuda:

Is that where you began mosquito fieldwork?

Kanuka:

Yes. But I had no previous experience in field-related research, so I had to build everything from scratch. Then, by chance, an opportunity arose.

At a mosquito research meeting held in the Amazon, I connected well with a young researcher from Burkina Faso in West Africa. Things progressed quickly, and we agreed to start a joint project there. It’s a French-speaking country with very few Japanese nationals, and I was the first Japanese infectious disease researcher to work there. Daily communication was difficult, but the local researchers welcomed me far more warmly than expected.

Looking back, choosing a country like Burkina Faso was ideal for someone like me—starting a new field with no prior connections.

I am, Ultimately, an Insect Researcher

Okuda:

What made you decide to conduct fieldwork in the first place?

Kanuka:

I don’t conduct research to treat patients or eradicate diseases. Of course, saving patients is the ideal outcome, but as I’m not a physician, I’m not directly on that path. I am, first and foremost, an insect researcher—a person driven by curiosity about insects. Wanting to understand their lives is what motivates my fieldwork.

For me, pathogens are also living organisms. When I observe the field, the pathogen, the mosquito, and the human all appear to coexist within a kind of crucible. Seeing their interactions makes me want to understand them—that remains the core motive for my fieldwork.

Okuda:

Do you have a specific “goal” within your research?

Kanuka:

It may sound strange, but ultimately, I don’t.

As I said earlier, I’m simply chasing what I’m absorbed in.

My family once encouraged me to pursue medical school, but I couldn’t picture myself treating patients—it just didn’t resonate with me. I thought I’d get bored, so I didn’t go. That feeling still hasn’t changed. When I go to West Africa, there are many patients, but helping them directly is not my role. There are many people dedicated to controlling and treating diseases; I’m happy being involved from a different angle.

I’m quite clear about this in my mind.

Future Goals

Okuda:

Could you tell us about your future goals or dreams?

Kanuka:

What interests me most now is creating organisms with specific traits—essentially “functional enhancement.” I’ve always been fascinated by making organisms. As a high school student, when I learned about genes and genomes, I thought, “You can do anything by linking four nucleotides!” That sparked my interest in biology. On the flip side, if you can cut and paste genes, you can theoretically create artificial organisms.

Okuda:

What kind of organism, for example?

Kanuka:

One idea is to create an organism that attracts mosquitoes—something like a decoy. Some people are more prone to mosquito bites than others, but we still don’t know why. Humans emit about 200 known odor compounds that attract mosquitoes, and finding the optimal combination among them is practically impossible.

But among mammals and birds, there are definitely species that get bitten more easily. By editing genomes and altering their genetic background, I want to create an organism highly attractive to mosquitoes. Ideally, the base organism would be livestock, making it a win-win for communities suffering from mosquito-borne diseases.

Okuda:

Some projects aim to reduce mosquito populations by releasing genetically modified mosquitoes. What do you think about those efforts?

Kanuka:

Using genetically modified Anopheles or Aedes to suppress mosquito populations has already been implemented in some places. It’s becoming part of public health strategy, so people like me are no longer needed for that phase. Honestly, I’m not interested in things others are already doing.

Okuda:

So as a researcher, you prefer to be the first?

Kanuka:

Perhaps. More simply, I find it boring when others have already started working on something. That’s why I often choose subjects or phenomena that no one else is paying attention to.

The biggest advantage is that if you fail, no one gets angry! (laughs) Since no one else is working on it, people just say, “Oh, that’s interesting,” and move on. It’s comfortable and fun that way.

Valuing What You Observe

Okuda:

Do you have any advice or comments for members of the Student Division of the Japanese Society of Tropical Medicine?

Kanuka:

Value the “phenomena” you see with your own eyes. When you witness something and your internal antenna reacts—grab onto it.

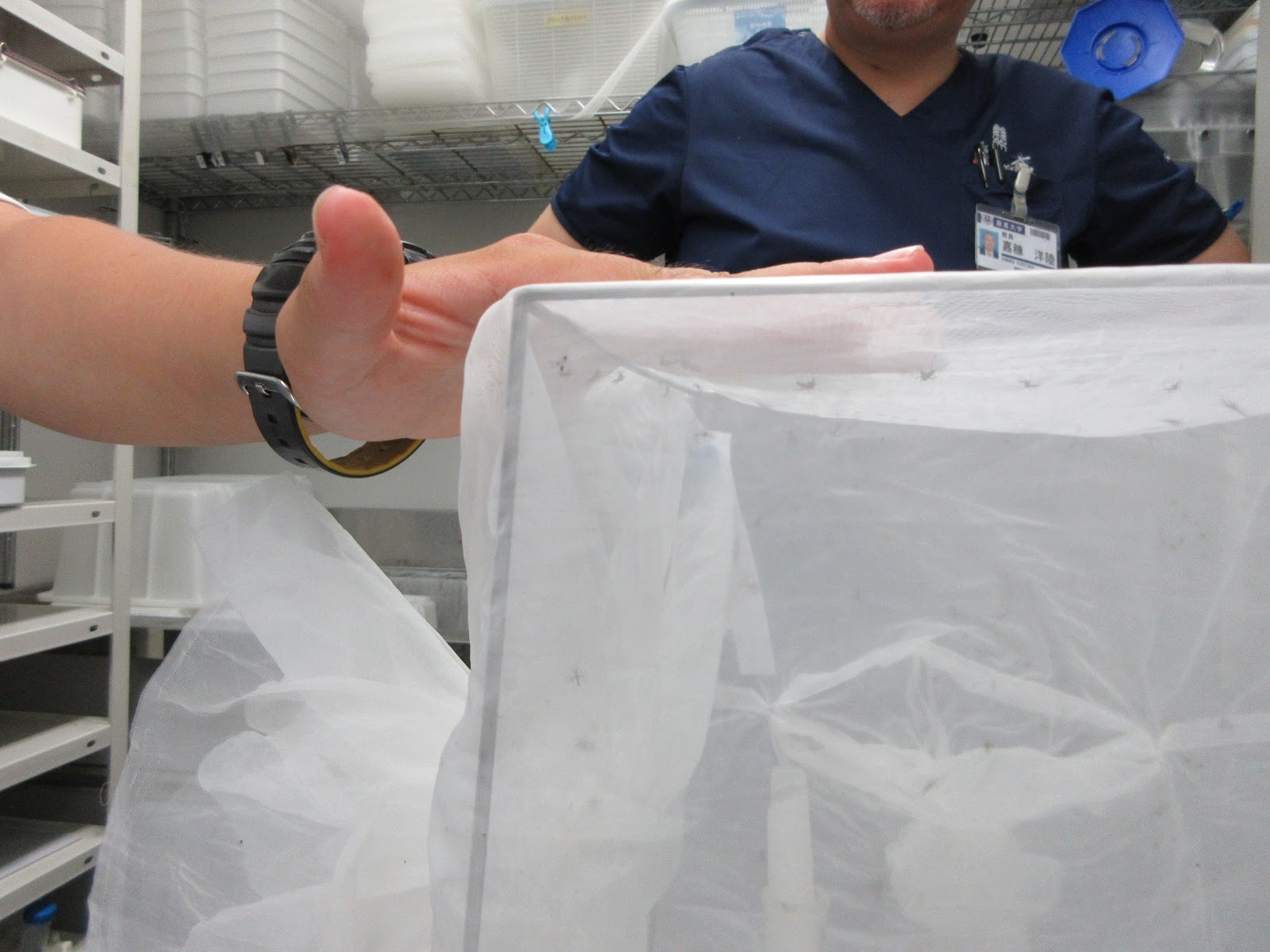

But you can’t experience that through a screen. You must use your own hands and feet; only then can you truly encounter real phenomena.

Observing patient symptoms up close, or seeing swarms of mosquitoes in Africa—it’s all the same at the core. When something resonates with you, never let it slip away. That’s what I want young people to keep in mind.

Sometimes my medical students say, “I can’t feel interested in patients or diseases.” When that happens, I tell them that it’s okay. It means that’s not your phenomenon—think of it as a kind of revelation. If so, lift your antenna again and keep searching for what captivates you.

Profile of Interview Participants

Dr. Hirotaka Kanuka

Professor, Department of Tropical Medicine, Jikei University School of Medicine. Born in Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture. Graduated from the University of Tokyo Faculty of Agriculture, Veterinary Medicine course in 1997; earned his PhD in Medicine from Osaka University in 2001. After working as a researcher at RIKEN, he began studying disease vectors at Stanford University. After returning to Japan, he joined the University of Tokyo and became Professor at the Research Center for Global Agromedicine, Obihiro University, in 2005. He has been Professor of Tropical Medicine at Jikei University since 2011. His motto is “You excel at what you love.” Author of Why Do Mosquitoes Attack Humans? (Iwanami Science Library).

Mitsuki Okuda

Third-year medical student at Nagasaki University. Born in Okayama City. Developed an interest in global health in junior high school and entered Nagasaki University as her first step. Currently conducting research in the Department of Bacteriology at the Institute of Tropical Medicine. Aspires to be both a clinician and a researcher specializing in infectious diseases. Enjoys outdoor activities such as boating, hiking, and cycling.